The Impact of the Student Debt “Crisis” on Housing: Five Takeaways for the U.S. Real Estate Industry

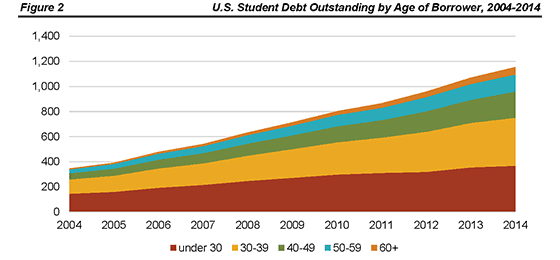

Between 2000 and 2014, the total volume of outstanding federal student debt in the U.S. nearly quadrupled to surpass $1.1 trillion, the number of student loan borrowers more than doubled to 42 million, and loan default rates among student borrowers rose to their highest levels in 20 years. The confluence of an unprecedented level of student debt outstanding with double-digit default rates on student loans has created widespread uncertainty as to whether the United States is facing a “student loan crisis.” Some economists have predicted that this indebtedness will potentially impact the broader economy by reducing consumer spending and potentially limiting long-term wealth creation opportunities for members of Generation Y.

However, there has been relatively little analysis of student debt’s likely impact on real estate markets—particularly the for-rent and for-sale housing markets.

In approaching this question, RCLCO contemplated the issue of rising student debt levels nationwide within the context of the economic and demographic forces shaping U.S. real estate in coming years.

The five primary takeaways from our findings are:

- Student debt affects more people to a greater degree than ever before, and will likely have a growing impact over time on the U.S. housing market.

- The debt burden has escalated disproportionately, with students at for-profit institutions carrying an outsized burden while traditional student borrowing has seen less change over time.

- Although borrowing makes economic sense for students who graduate, it appears that student debt has a real and growing impact on economic behavior patterns, particularly among younger households.

- Student debt is likely constraining the for-sale housing market across age groups and income levels because existing debt loads reduce additional borrowing capacity.

- While rising student debt, by making homeownership more difficult, may create additional and/or prolonged demand for rental housing, it can also have a meaningful negative impact on rental affordability for low- and middle-income renters and renters in more expensive markets.

The full article characterizes the nature of this debt—who holds it and in what amounts—and evaluates market data relative to an actual or likely future change in housing marker behavior and performance.

Student debt affects more people to a greater degree than ever before, and will likely have a growing impact over time on the economic behavior of borrowers.

Between 2000 and 2014, the total volume of outstanding federal student debt in the U.S. nearly quadrupled to surpass $1.1 trillion, the number of student loan borrowers more than doubled to 42 million, and loan default rates among student borrowers rose to their highest levels in 20 years. Recent data from the Federal Reserve Board of New York illustrates the nature of this debt:

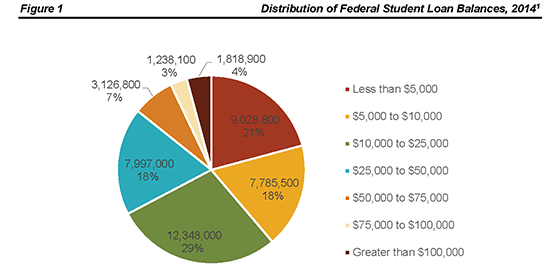

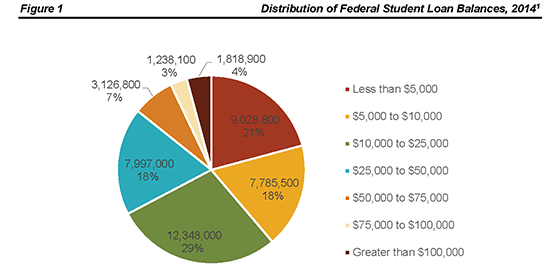

- At the end of 2014, there were estimated to be 43.5 million people in the U.S. with $1.15 trillion in total student debt outstanding.

- The distribution of loan balances for these 43.5 million borrowers is detailed in Figure 1 below.

- In 2004, 25% of 25-year-olds had student debt. In 2014, this proportion had grown to 45%.

- Over the same time period, average student debt balances for individuals with student debt doubled, growing from approximately $10,000 to over $20,000.

- Recent graduates from four-year colleges had average student debt balances over $28,000 in 2014; for the Class of 2014, two-thirds are estimated to have student debt outstanding at graduation.

- At the end of 2014, 68% of all student debt outstanding in the U.S. was held by borrowers aged 30 or older, and older Americans have continued taking on student debt—approximately 37% of originating student loan borrowers each year are 30 years of age or older.

Source: FRBNY; Equifax

While homeownership, particularly among Millennials, has been declining for years, available data suggests that Millennials who also carry student loans are even less likely or able to purchase a home, and increasingly are being forced to make economic tradeoffs to accommodate rising student debt levels.

Student debt is not just an issue for Millennials. Today, the majority of this outstanding debt is held by members of Generation X (people born between 1965 and 1980), who have been experiencing adverse economic outcomes related to student debt for over a decade, according to our analysis. Gen X households have been experiencing falling homeownership rates, limited income growth potential, and rising student debt balances over the past decade. In fact, RCLCO’s research indicates that Gen X is largely responsible for the sluggish performance of the for-sale housing market following the Great Recession.

The ramifications of this trend are far-reaching and likely to continue, as educational attainment levels continue to rise and U.S. officials explore ways to provide greater access to higher education to all Americans.

Source: FRBNY; Equifax

The debt burden has escalated disproportionately, with students at for-profit institutions carrying an outsized burden while traditional student borrowing has seen less change over time.

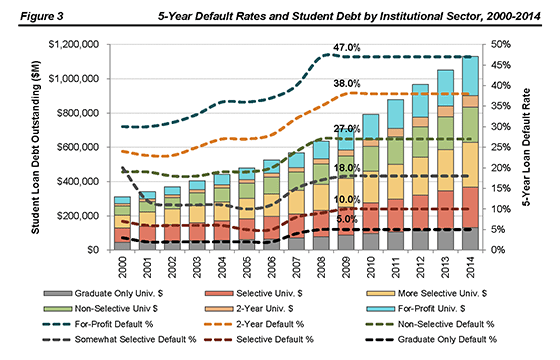

A Brookings Institution study[2] released in September 2015 argues that the student loan crisis, to the extent there is one, is actually concentrated primarily among so-called “non-traditional” borrowers at for-profit and community colleges. “Non-traditional” borrowers are older, less educated, less affluent, and attend programs they are less likely to complete. Post enrollment, they are more likely to live in or near poverty and to experience weak labor markets. The number of non-traditional borrowers began to increase in the mid-1990s as enrollment in for-profit institutions escalated, and then surged during the Great Recession as the weak labor market encouraged many to return to school, and to borrow to do so. Figure 3 below highlights this phenomenon.

- The data suggests that despite substantial borrowing increases across institution types, the increase in student loan defaults is most acute among non-traditional borrowers enrolled at for-profit, two-year, and non-selective institutions.

- In 2011, non-traditional borrowers represented 50% of the cohort beginning loan repayment, yet accounted for 70% of defaults.

Recent rates of default are unlikely to persist as enrollment patterns have normalized and employment growth continues. From 2010 to 2014, the number of new borrowers at for-profit schools fell by 44% and by 19% at two-year institutions. By contrast, default rates among “traditional” student borrowers—who comprise the vast majority of the federal loan portfolio—have moderated somewhat following a rather sharp uptick during the Great Recession.

Source: Brookings

Although borrowing makes economic sense for students who graduate, it appears that student debt has a real and growing impact on economic behavior patterns, particularly among younger households.

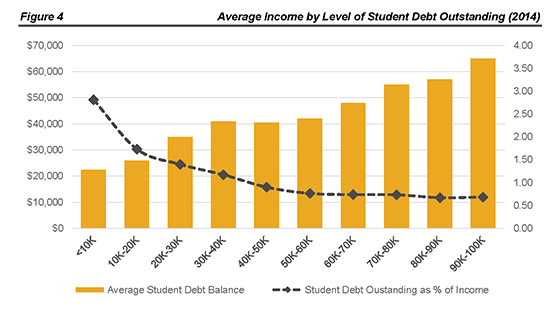

The data presented in the previously mentioned Brookings study, as well as data collected during RCLCO’s analysis, illustrate that traditional borrowers have substantially higher earnings than the population in general and that borrowers with higher levels of debt tend to have higher earnings. Overall, student debt still acts as a signifier of upward social mobility and higher educational attainment, particularly for those earning advanced degrees. The chart below shows the mean student loan balance of four-year degree recipients two years after entering loan repayment, broken out by annual income categories. There is a strong positive relationship between earnings and student debt balances.

Source: FRBNY

Ability to pay down outstanding student debt principal is attributable to post-graduation income: the average principal balance on loans for borrowers earning below $40,000 has only been reduced by 3-4% after five years of entering repayment. Student loan principal balances for those earning greater than $80,000 per year, on the other hand, have been paid down by 27% after five years of payments, suggesting that higher disposable income levels allow student borrowers to pay down principal more rapidly, while still being able to cover other expenses.[3]

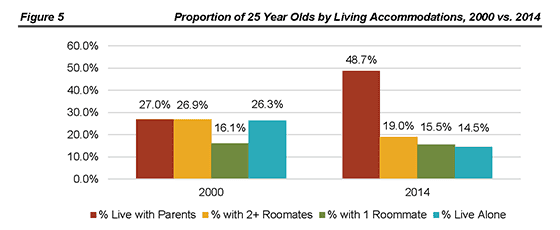

Although not directly attributable to rising student debt levels in the U.S., over the past decade, an increasing share of young Americans—many of whom are facing expensive student loan payments, stagnant wages, and/or under- or unemployment—have opted out of the housing market altogether, choosing instead to move back into their parents’ homes. As the share of those under 30 with student debt has increased, so has the proportion of young people living with their parents:

- In 2014, 49% of 25-year olds lived with their parents, compared with 27% in 2000.

- Among 30-year olds, 31% lived with their parents in 2014, compared with 19% in 2000.[4]

Source: Census, ACS (2013-2014)

The long-term impact of student debt on the housing market is uncertain, but student debt appears to be constraining the for-sale housing market across age groups and income levels.

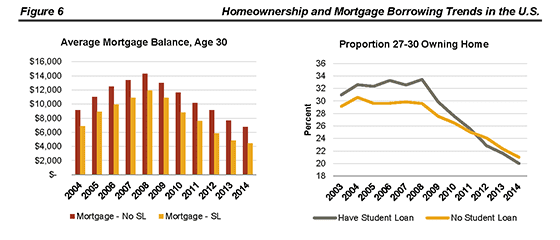

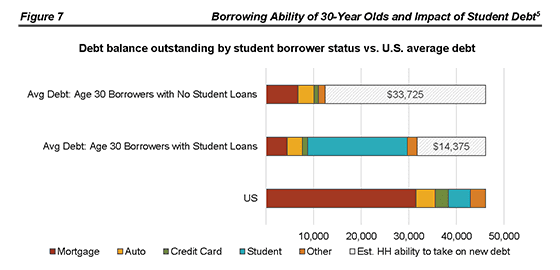

In a reversal from historical trends, people 30 years old and younger with student debt outstanding are less likely to own a home today than their peers with no student debt. While homeownership, particularly among Millennials, has been declining for years, RCLCO’s analysis of data from the Federal Reserve Board of New York shows that Millennials who also carry student loans are even less likely or able to take on other types of household debt than their peers, including but not limited to mortgage debt.

Source: FRBNY; Equifax

As borrowers enter student loan repayment, their ability to take on additional debt is constrained, either as a result of reduced disposable income or because taking on additional debt is considered to be an unwise lending or borrowing decision. Among 25-year olds with no student debt, overall debt levels are substantially lower, although home-secured (mortgage) levels are appreciably higher.

Source: FRBNY; Equifax

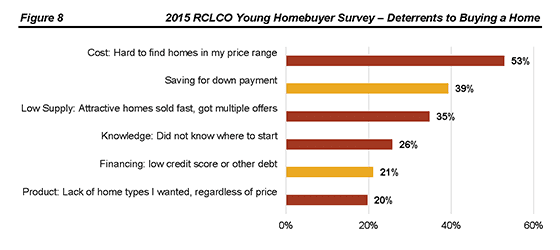

RCLCO recently conducted a consumer survey of first-time homebuyers aged 40 or younger which asked respondents to identify the key challenges they faced in their purchase. 39% of respondents cited difficulty saving sufficient money for a down payment, while 21% cited lack of credit as a deterrent. Figure 8 below summarizes survey responses. Similarly, data from the Federal Reserve Board of New York shows that student borrowers have lower credit scores over time than their peers with no student debt, potentially discouraging or even prohibiting student borrowers from obtaining the leverage needed to make major household investments.

Source: 2015 RCLCO Young Homebuyer Survey

Generation X borrowers, who own 50% of all student debt outstanding in the U.S., have already and will continue to experience negative economic outcomes related to student debt, such as reduced income growth potential, declining homeownership rates, and higher loan default rates. According to the latest report from the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies, “The national homeownership rate slid for the 10th consecutive year in 2014 to 64.5%, and continued to fall in early 2015 with a first-quarter reading of just 63.7%—the lowest quarterly rate since early 1993. The homeownership rate for 35-44 year olds has fallen most and is down 5.4% points from the 1993 level and back to a level not seen since the 1960s. In fact, the national homeownership rate remains as high as it is only because the baby boomers (born 1946–64) are now in the 50-plus age groups when homeownership rates are high, and because owners aged 65 and over have sustained historically high rates.”[6]

According to Fannie Mae’s National Housing Survey for the fourth quarter of 2014,[7] 82% of respondents thought that owning made more financial sense than renting. Even among renters, 67% agreed with this statement. Among renters aged 18–39, 92% expected to buy homes eventually, but 62% of renters aged 18–39 reported that getting a mortgage would be difficult for them.

Essentially, student debt makes it more difficult to transition from renting to owning, even among high-income households, by reducing the amount of additional debt that can be taken on through a mortgage, increasing mortgage borrowing costs, and reducing income available to save for a down payment. As such, student debt also reduces the price of homes that households can afford. Generally, our analysis suggests, rising student debt has and will continue to delay the entrance of younger and less affluent households into the for-sale housing market.

While rising student debt is supportive of rental housing by potentially delaying renters’ ability to purchase homes, it can have a meaningful negative impact on rental affordability for middle-income renters and renters in more expensive markets.

According to Fannie Mae’s National Housing Survey for the fourth quarter of 2014,[8] in 2013, 39% of households aged 20–39 carried an outstanding student loan balance, up from 22% of same-aged households in 2001. While nearly two-thirds (64%) of people aged 20–39 with student loan debt owed less than $25,000 in 2013, a fifth (19%) had balances of at least $50,000—more than three times the share in 2001. In 2013, 8% of all households repaying their student loans had high debt burdens (payments exceeding 14% of monthly income), while the share of renters aged 20–39 with these debt burdens was especially high at 19%. Interestingly, over one-half of households in their 20s and 30s with student loan debt in 2013 did not have four-year college degrees—and therefore are particularly likely to experience high student debt burdens compared to college graduates.

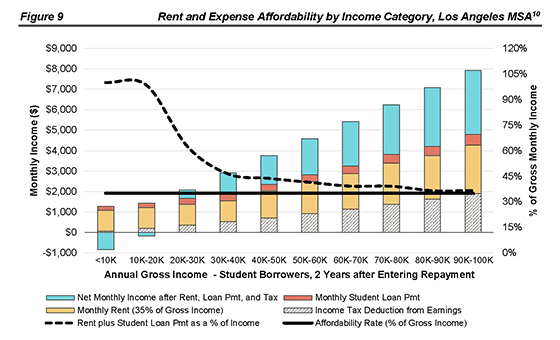

RCLCO’s analysis suggests that renters’ ability and willingness to pay for housing is negatively impacted by student debt, particularly for middle- and low-income households, as a result of rising student debt burdens affecting a growing share of renters, coupled with rising housing costs nationwide. Beginning with data from the Federal Reserve Board of New York that provides average loan balances by income band, RCLCO conducted its own analysis of renter affordability, focusing on the potential impact of monthly student debt payments on household spending. Specifically, we attempted to identify the types of renters most likely to choose less expensive housing in order to offset monthly student loan payments.

RCLCO conducted this analysis to try to answer the question of whether rental decisions were tied to levels of student debt. Using data from the 2013 and 2014 American Community Survey (1-Year Samples) and Axiometrics, we estimated median monthly rent for each income band. We calculated monthly student debt payments, assuming a 15-year repayment period at an annual fixed interest rate of 5%, and using the average loan balances by income category provided in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York dataset.[9] We then applied weighted average tax rates, provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, to each income band, to show the amount of “take home” pay an individual would receive at each income level, after netting out primary fixed expenses: rent, student loan payments, and taxes.

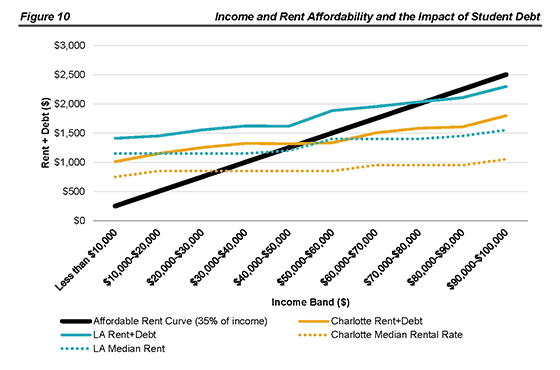

We assumed an “affordability” threshold of 35% of gross monthly income—the maximum amount any renter would be willing to pay for housing costs—to show the degree to which housing plus student debt causes the same affordability issues as housing alone without debt. (Essentially, we bundled student debt and housing costs together and treated them as one fixed cost to test their affordability against a generally accepted housing affordability metric.) In this hypothetical analysis, we assume that the two fixed costs act as substitutes in household budgeting and decision making. If a household cannot afford to pay 35% of its income on rent, it cannot afford to pay 35% of its income on rent plus student debt and will seek out lower-priced rental housing in response.

Source: Census, ACS (2013-2014)

The greatest impact of student debt will be felt by middle-income renters, who, unlike low-income renters, have some flexibility to choose between available housing options and price points, and, unlike high-income renters, are governed primarily by affordability in their housing decisions.

- These renters are more likely than low- or high-income households to pay rents tightly in line with what they can afford, and therefore seek rents below what they would otherwise pay in response to student debt.

- As such, student loan payments can have a sizeable impact on housing choices, in terms of cutting into disposable income and forcing householders to make economic tradeoffs to make ends meet.

The definition of middle-income renters varies between markets, but Figure 10 shows that in this middle-income section, the curves do not just intersect with the 35% of gross income curve, but also flatten out. This flattening represents the impact the economic tradeoffs have on total expenditures for rental + student debt payments. People begin to save on rents in response to their student debt outlays, flattening the curve so that student debt takes up a portion of expenditures that would have gone only to rent. This finding suggests that in the middle-income range, renters are substituting rental payments for student debt, paying off student debt while living in less expensive housing instead of living in the rental housing that their incomes would suggest they can afford.

It is also worth mentioning that among low-income renters, it appears that even before making monthly student loan payments, low income earners often are forced to pay much more than they can “afford” for rental housing. For low-income households with student debt, the situation is exacerbated. Because these low-income households are typically already renting the most affordable housing in the market, it is likely that these households, when burdened by student debt, may be more likely to choose to live with family or roommates than middle- or high-income renters—or low-income renters without student debt—do.

Source: RCLCO; ACS; BLS; Axiometrics

Conclusion

While homeownership, particularly among Millennials, has been declining for years, RCLCO’s understanding of the trends discussed in this article leads us to consider that rising student debt levels across age and income groups in the United States could potentially be impacting housing decisions, particularly among renters, by making it more difficult to transition from renting to owning. Despite evidence that the desire to own homes in America has not necessarily diminished, homeownership has fallen over time, likely as a result of many complex and compounding factors, including rising student debt burdens nationwide.

Among households in low- and middle-income categories, who are more likely to be renters as a result of limited means to purchase a home (even before considering rising student debt burdens), student loan payments are most likely to have a significant impact on housing choices because of the need to make more difficult economic tradeoffs.

In the real estate industry lately, rental housing affordability has become a major topic of discussion, as low- and middle-income households are increasingly priced out of market-rate rentals, while many have hypothesized that the situation will continue to worsen in the most expensive markets. Considering that a growing share of households today are burdened with student debt, it will become increasingly important to understand the impact that student debt has on affordability and housing decisions in the United States.

1 Federal Reserve Board of New York, Equifax

2 http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/projects/bpea/fall-2015_embargoed/conferencedraft_looneyyannelis_studentloandefaults.pdf

3 Federal Reserve Board of New York, Equifax

4 Census, American Community Survey

5 Federal Reserve Board of New York, Equifax

6 http://www.jchs.harvard.edu/sites/jchs.harvard.edu/files/son_2015_key_facts.pdf

7 http://www.fanniemae.com/portal/research-and-analysis/housing-survey.html

8 http://www.fanniemae.com/portal/research-and-analysis/housing-survey.html

9 This is clearly an oversimplification – made for the purposes of this analysis – of actual student loan payments, which doesn’t account for interest-only payments, increasing balances, or loans that are delinquent or in default.

10 Census, ACS 2013-2014

Article and research prepared by Cari Smith, Vice President, and Steven Wang, Senior Associate.

RCLCO provides real estate economics and market analysis, strategic planning, management consulting, litigation support, fiscal and economic impact analysis, investment analysis, portfolio structuring, and monitoring services to real estate investors, developers, home builders, financial institutions, and public agencies. Our real estate consultants help clients make the best decisions about real estate investment, repositioning, planning, and development.

RCLCO’s advisory groups provide market-driven, analytically based, and financially sound solutions. Interested in learning more about RCLCO’s services? Please visit us at www.rclco.com/expertise.

Disclaimer: Reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the data contained in this Advisory reflect accurate and timely information, and the data is believed to be reliable and comprehensive. The Advisory is based on estimates, assumptions, and other information developed by RCLCO from its independent research effort and general knowledge of the industry. This Advisory contains opinions that represent our view of reasonable expectations at this particular time, but our opinions are not offered as predictions or assurances that particular events will occur.

Related Articles

Speak to One of Our Real Estate Advisors Today

We take a strategic, data-driven approach to solving your real estate problems.

Contact Us