“Deeper and Deeper and Deeper”: Sizing America’s Condominium Markets

In this space over the past six months we have discussed how to prepare for the increasing condominium market opportunity and how to manage the cyclicality of this high risk-high reward space, and the wide demographic variety of condo owners/buyers that comprise this market and strategies for segmentation, and we have profiled condominium projects that are targeting these buyer cohorts today.

Now the proverbial $100,000 question—how do you determine which buyer segments are available in any given market and how deep is the buyer pool? Further, how do you scale a proposed development, switch, or conversion to match that reality?

In this fourth and final installment on consumer segmentation in the condominium market, we explore RCLCO’s market segmentation approach and a few examples of how this analysis was deployed in selected U.S. cities, and highlight here four findings gleaned from deploying this methodology in markets nationwide.

- The empty nester market is a significant portion of demand (40%+ in some markets), but attracting empty nester buyers requires careful alignment of location, product, and amenities, at a compelling price point relative to their current home. In essence, there are lots of possible and interested buyers, but they have little urgency to move out of their current home until the “stars align” in each customer’s unique way.

- The “move-up,” or “never nester” market, on the contrary, is deeper and with greater willingness to pay for lifestyle than many think. In this cycle, however, many of these buyers may have missed the “first move” and will be buying for the first time but with more spending power and more discernment as to what they purchase.

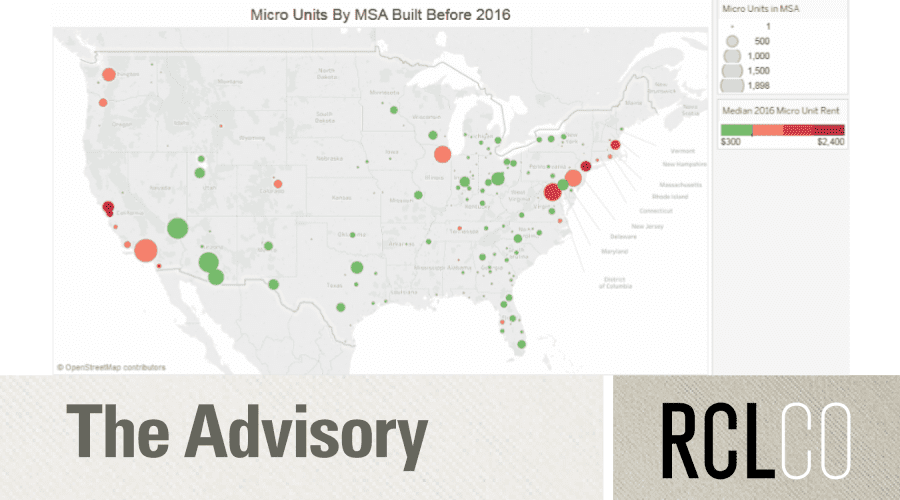

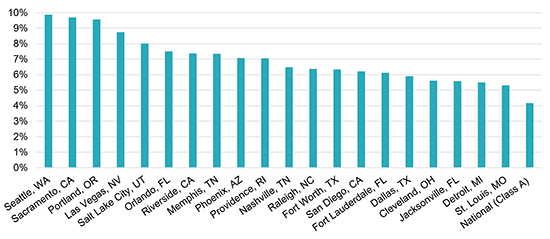

- The trend toward acceptance of smaller units for projects oriented towards young professionals, now well documented as viable in the rental apartment space, seems to have legs in the for-sale markets as well, at least in high-cost markets.

- Look out for the “stroller brigade”—observed in New York City in the last cycle, but the “push through” to kindergarten is spreading to more markets. While the “Urban Family” market may currently represent a small component of condo buyers, it’s increasingly common for couples approaching the transition to the family lifestage to still consider purchasing a condo—so long as they can envision starting a family in their new home. The size of this segment is probably underestimated in the analysis below, as the rate of this structural change is not yet knowable.

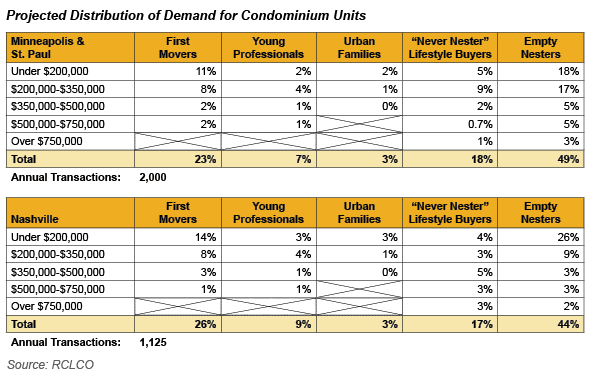

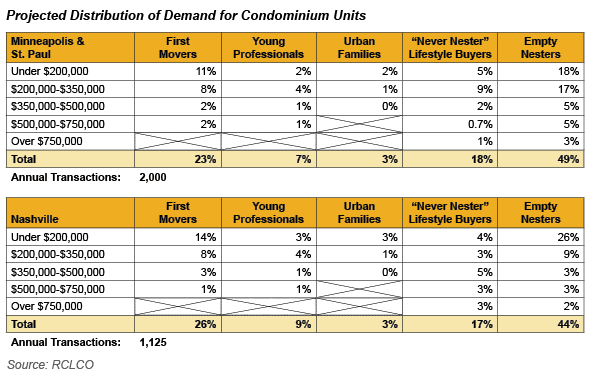

While many factors determine the volume of new condo sales in a market, an effective segmentation analysis can forecast the likely transaction activity as well as the likely composition of buyers. To illustrate the variation from one market to the next, RCLCO chose one large and one medium size market that have demonstrated increasing acceptance of high-density housing in recent years.

This projection of annual activity suggests the total condo transaction volume (both new and resale) that should occur if appropriate and compelling housing options are available, though in newly urbanizing markets much of this demand will materialize only as new product is introduced into the market.

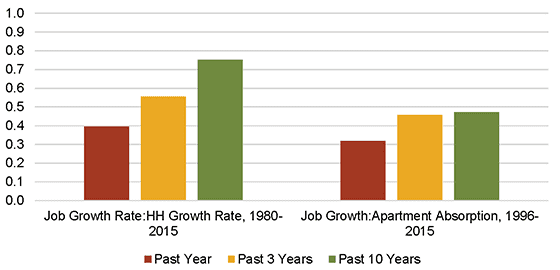

RCLCO’s approach to segmentation analysis uses Census data to understand the depth of market not just by age and income, but by lifestage and purchasing power. Similar to a typical demand analysis, it relies on demonstrated historical data about how often each household segment moves, how likely they are to own rather than rent, and what percentage may choose to purchase a condo over other housing options.

The results provide a relatively conservative baseline of potential annual condo transactions in the given market, with the understanding that any continued shift in preferences toward a higher-density, more urban lifestyle might produce substantial upside, and reveal which market segment or combination of segments comprises the deepest market opportunity. This analysis produces an annual average projected rate of sales, realizing of course that in the “mature” segment of the market cycle actual sales may peak at a level quite a bit higher than this.

Both Minneapolis-St. Paul (Hennepin and Ramsey counties) and Nashville (Davidson County) demonstrate a similar distribution of buyers across the lifestage spectrum, with the strongest market potential in the First Movers (Singles and Couples age 25-30), Never Nesters (Singles and Couples Age 35-54), and Empty Nesters (current homeowners 55 or older). This begins to suggest that two to three distinct projects may be most effective at targeting the available segments.

Forecasting future condominium demand even more precisely has become a lot easier and more cost efficient with the growing availability and low cost of using consumer research panels. We now have the ability to solicit potential interest in condominiums among prospective home buyers in any given market at relatively low cost. An example of output from this type of research in Washington, D.C., is demonstrated here.

With better information regarding the size of the potential market, two questions are answerable:

- How is a prospective development, conversion, or switch scaled to the market?

- Should a newly conceived development project target one market segment or many, a question partially addressed in a previous Advisory?

The question of sizing depends in part on the range of alternatives in a given market (including resales) and the competitive potential of the proposed development’s location, as well as the sponsor’s ability to effectively design, deliver, and market a project that might outperform the competition.

Our experience is that a condominium project should not anticipate a marketing window of more than 36 to 42 months, in most cases including a period of pre-sales, and hopefully not lasting long after delivery. If this is the case, the potential transaction volume in a market like Minneapolis that a project can compete for is roughly 7,000 (2,000 per year times three and a half years). This would, of course, assume that the project is designed for and marketed to all demographic and price segments.

Resales always capture some of the market activity, as they usually represent good value (at least relative to location) and are available more immediately. This might represent as much as 85% to 90% of transaction activity in a market like Chicago or San Francisco with a long history of condominium development, but as little as 60% or less in a market like Minneapolis or Nashville where there is less existing inventory or the inventory is of lower quality. In the case of Minneapolis, we might estimate that 30% to 40% of the potential transactions would represent a market size for new development (in the last cycle this peaked at an even higher share), or roughly 2,500 units.

The question then becomes: how might the sales be shared among competing projects? The simplest way to forecast this potential is a straight “fair share” analysis—simply to study the number of competitors (other new condominium developments and conversions) and suggest that each would share sales equally. In this case, if it were likely that there are 20 potential competitors, the proposed development in question would capture 5% of new sales in this price range, and thus the appropriate scale of a new project would be 125 units (5% of the 2,500 potential new transactions over a 36 to 42 months period).

Of course not all projects compete equally, with competitive potential driven by project scale, sponsor, location, price positioning, marketing, and many other factors. RCLCO recommends development of a detailed “gravity model” to reflect the competitive potential of the asset against the known and anticipated competition, and reflecting the case that some projects will capture more than their fair share and some less–in this example the appropriate scale might be smaller or larger than the 125 units suggested above.

The final level of analysis is to evaluate the trade-off between focusing on one or two specific market segments with a proposed project or alternatively trying to be “all things to all people.” The analysis is similar. If we believe that a submarket or site is appropriate to upscale empty nesters, for instance, we can assume that some portion of roughly 560 potential transactions—annual sales of units priced $500,000 and over to empty nesters (160) times three and a half years—is available to the project in question.

Assuming that new projects might capture as much as 50% of the demand, and if only three or four competitors including the subject property are positioned to attract this customer, we might conclude that there is sufficient market support for a highly targeted project of 70 units (25% of 280 projected new sales over the marketing window).

If any one market segment is too small to support a targeted project (a strategy that is often preferable from the perspective of achieving strong emotional response from the anticipated buyer group), a new development may need to target more than one and perhaps several segments. This is often necessary to align with potential demand and manage market risk.

There are, of course, numerous remaining questions to be answered relative to market segmentation:

- If the market supports it, are different market segments better accommodated in one building “wedding cake style,” by different tiers of units on different floors, or mixed throughout the building?

- Can condos and rentals be accommodated in a shared mixed-use building?

- Can adjacent and related condominium buildings share amenities? Or can amenities be shared between rental and condo buildings and if so which amenities?

- Does hotel branding and servicing still drive performance in terms of pricing and market penetration?

- What is the impact of building size/number of units on exclusivity/pricing?

- How small is too small in terms of unit size for any given market, and does smaller necessarily result in better economic performance?

Stay tuned in this ongoing exploration of one of real estate’s most promising but most challenging product types.

Article and research prepared by Adam Ducker, Managing Director, and Erin Talkington, Vice President.

RCLCO provides real estate economics and market analysis, strategic planning, management consulting, litigation support, fiscal and economic impact analysis, investment analysis, portfolio structuring, and monitoring services to real estate investors, developers, home builders, financial institutions, and public agencies. Our real estate consultants help clients make the best decisions about real estate investment, repositioning, planning, and development.

RCLCO’s advisory groups provide market-driven, analytically based, and financially sound solutions. RCLCO’s Urban Real Estate Group produced this newsletter. Interested in learning more about RCLCO’s services? Please visit us at www.rclco.com/urban-real-estate.

Related Articles

Speak to One of Our Real Estate Advisors Today

We take a strategic, data-driven approach to solving your real estate problems.

Contact Us