Infrastructure Financing in Master-Planned Communities

One of the biggest challenges of developing a large-scale master-planned community (MPC) is figuring out how to pay for the huge upfront infrastructure costs. With banks and other traditional sources of development finance hesitant to invest in long-term projects and municipalities unable or unwilling to provide extensions of existing infrastructure, developers must often use creative financing mechanisms to help fund roads, water and sewer lines, and other critical infrastructure improvements in support of new community development. Some of the public finance methods being employed in Texas and Florida, two states where there are a significant number of successful large-scale MPCs, are indicative of the way such infrastructure will likely be financed in the future.

Texas

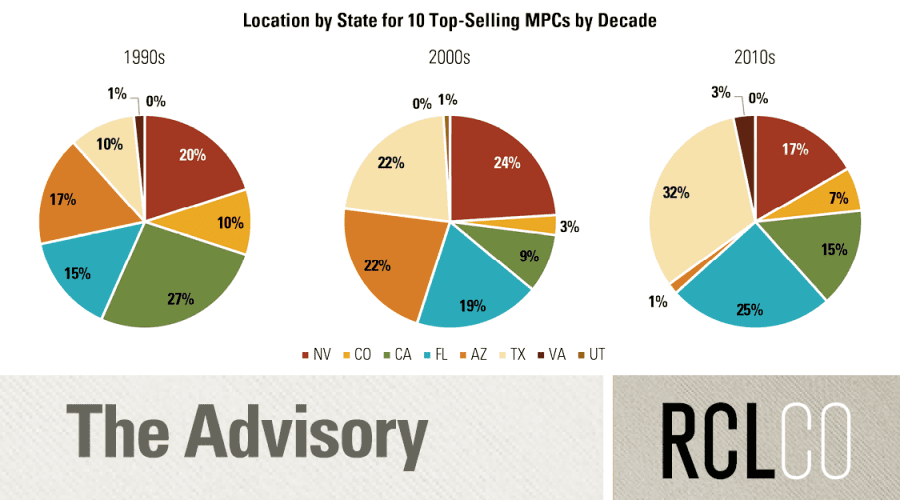

RCLCO’s 2012 Master-Planned Community Survey found that nine of the top 20 selling communities in the United States were located in Texas, with eight in the Houston area alone. The financing of infrastructure improvements in these communities has been a major factor in their success. Due to restrictions set forth in the Texas State Constitution that make it difficult for cities and counties to incur debt and collect taxes for infrastructure development, special districts have been used to finance all or part of the required utility and community support facilities, which in some cases include certain amenities such as parks. The principal tool for financing community infrastructure in Texas is the Municipal Utility District (MUD), with Public Improvement Districts (PID) playing a similar but relatively new role.

Special Districts in Texas

The basic purpose of a MUD is to provide services such as sewer, water, and drainage to areas where city and county services are not available. A MUD can also fund parks, street lighting, some roads, and fire prevention facilities. Each phase of infrastructure in a MUD is initially funded by the developer, but the developer is ultimately reimbursed for these expenditures from the sale of tax-exempt bonds, which are serviced through an ad valorem tax on property owners utilizing the newly constructed infrastructure. As subsequent phases are built out, more bonds are sold, the proceeds of which are used in part to reimburse the developer. This cycle continues until the MUD is completely built out. The bonds must be approved by the Attorney General of Texas, and meet stringent financial feasibility requirements set forth by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. In addition to the ad valorem tax, property owners also pay monthly water and sewer user fees, which are used to maintain the system. A MUD typically lasts for 20 to 30 years, after which the district is usually annexed by an adjacent county or municipality. Municipal Utility Districts are the main mechanism for infrastructure financing, and have been used in almost every large community in Houston.

A PID is a public/private financing mechanism for land development, and is relatively uncommon in Texas, though it is increasing in popularity. PIDs are governed by a city or county, whereas MUDs are governed by an elected board of directors. Unlike a MUD, PID funding can occur before development takes place by issuing bonds to fund up-front costs like engineering and road construction. A PID also has a longer list of eligible improvements in addition to those allowed for MUDs, including mass transit, libraries, pedestrian malls, and affordable housing. The other main difference is the source of funding. PID bonds are serviced through a special assessment, rather than ad valorem taxes, on homes within the district. Unlike property taxes, which are calculated based on a percentage of the assessed value of the property, a special assessment is expressed as a fixed amount. Therefore, the homeowner’s monthly payment of the assessment remains constant until it is paid off. While a MUD can simply increase the MUD tax rate on other homeowners (up to a certain point) if a homeowner defaults, a PID may only seek payment from the defaulting property owner if he or she does not pay the assessment.

Effects of Special Districts in Texas

Municipal Utility Districts serve as an efficient and low-cost mechanism for financing infrastructure development and have allowed various areas in Texas, particularly Houston, to accommodate substantial household growth in recent years while maintaining relatively affordable home prices. In many other states, the entitlement process can be very lengthy, particularly when developers are dependent upon the local municipality to deliver needed services to a proposed development, and the carrying costs incurred by developers are passed on to the homebuilder, and ultimately the homeowner. MUDs, once approved, effectively allow developers to pace the delivery of new infrastructure with what the market will bear, and remove the burden from the public sector, reducing entitlement risk and costly delays that ultimately get passed on to the homebuyer. Furthermore, since much of the major infrastructure costs are reimbursed to the developer through the sale of bonds serviced by the homeowner MUD tax, homeowners pay over time for the community’s infrastructure in lieu of paying for the infrastructure up-front in the form of a higher home price.

Overall, MUDs and PIDs can present a “win-win-win” situation for municipalities, developers, and consumers by allowing for low-cost, predictable infrastructure financing for new master-planned communities. The public sector benefits mainly through the development of high-quality infrastructure at minimal cost and risk to city and county governments. Developers benefit by mitigating many of the entitlement risks associated with more lengthy permitting processes as well as the financing risks that come with self-financing all infrastructure, the cost of which would be reflected in higher lot and home prices. Consumers benefit through lower home prices, enabling households with more moderate incomes to afford new homes in high-quality MPCs.

Florida

Special Districts in Florida

In Florida, Community Development Districts (CDDs) have been an important resource to pay for large-scale community development infrastructure. CDDs are special purpose districts in which developers issue bonds, with bonds repaid using special assessments levied on homeowners. Although primarily used for roads, sew ers, and utilities, some developers have even financed amenities, including golf courses and clubhouses. For example, CDDs have been creatively used at The Villages, the top-selling master-planned community in the country in 2012 based on RCLCO’s annual survey.

Without CDDs, many large-scale developments would never move forward in Florida. But CDDs became very controversial following the great recession and associated collapse of the real estate market, with 122 districts defaulting on almost $3 billion worth of bonds between 2008 and 2010. Many communities were unable to service their CDD bonds after lot and home sales slowed dramatically. When banks and other financial institutions seized land from developers, existing owners were forced to pay higher assessments in order to service initial CDD bonds. Needless to say, this has not helped their reputation. Nonetheless, corresponding with the residential real estate recovery, well-conceived new large-scale community developments, such as Tavistock’s Lake Nona development in Orlando, have successfully created new CDDs that are functioning as intended, where they are supported by strong residential sales.

The Future of Special Districts

In Texas, Municipal Utility Districts will likely continue being employed on a massive scale to encourage development of new communities. Given their recent success, MUDs will likely be preferred over public-private partnerships or municipal financing of infrastructure development. MUDs will continue contributing to less expensive lot development, and thus lower home prices, for the foreseeable future. It is similarly likely that CDDs will continue to be an important source of infrastructure financing in Florida, and that similar approaches will need to be used in other states as well, since there is great demand for master-planned communities and no single source of infrastructure finance for such projects.

Article and Research prepared by Gregg Logan, Todd LaRue, and Evan Caso of RCLCO’s Community and Resort Advisory Group.

RCLCO’s advisory groups provide market driven, analytically based, and financially sound solutions. Interested in learning more about RCLCO’s Community and Resort Advisory Services, please contact Lori Cabrera at lcabrera@rclco.com or (407) 515-4998.

Related Articles

Speak to One of Our Real Estate Advisors Today

We take a strategic, data-driven approach to solving your real estate problems.

Contact Us